Meaning Dynamics

Part 1: Developing meaning dynamics

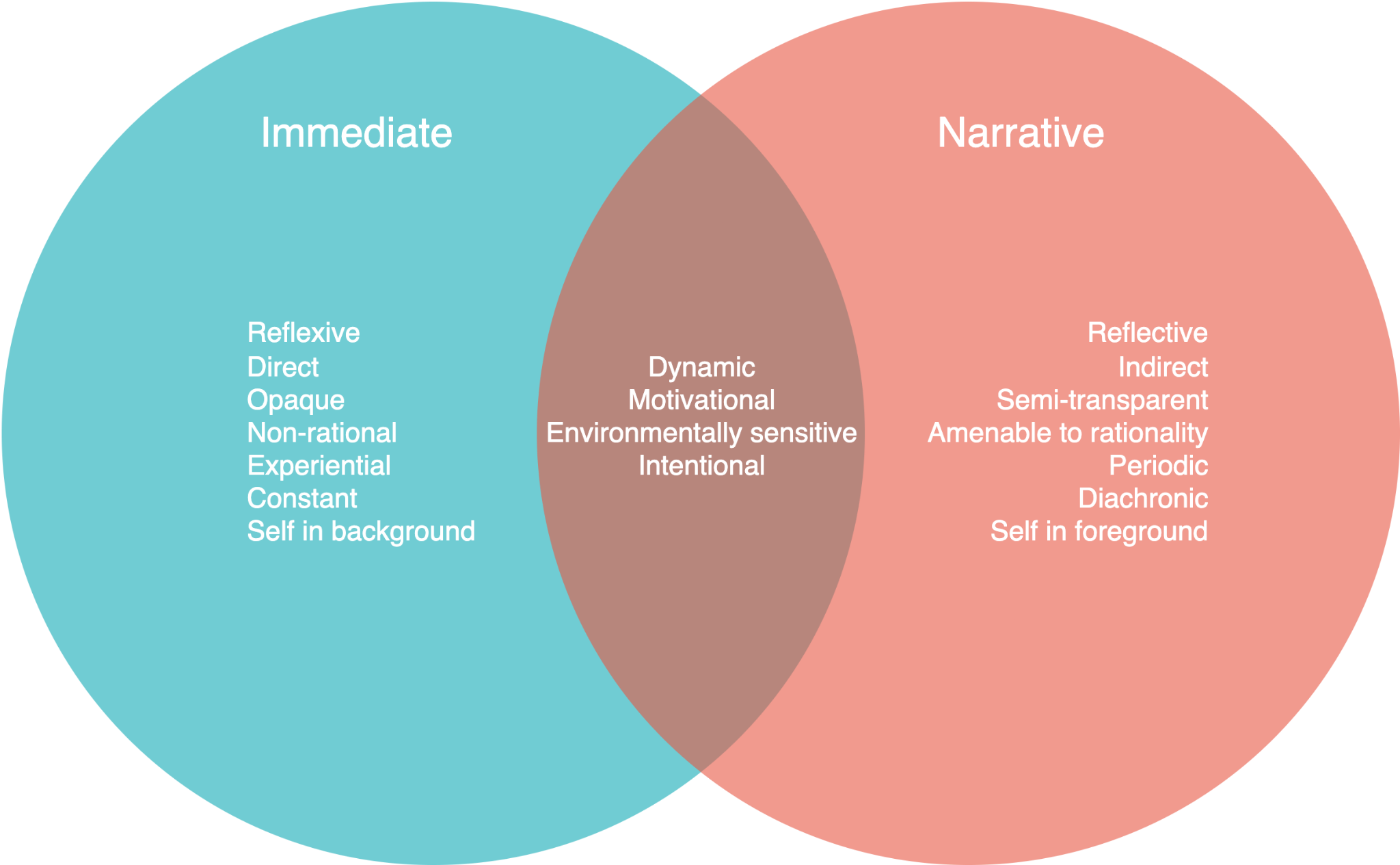

Meaning in life is a complex dynamical process. Not only does mankind “search for meaning”—it also finds meaning in every moment. This meaning does not reveal itself as a series of properties of static objects in some objective universe, but through the direct experience with which we necessarily construct our understanding of our world and the things within it. In other words, we do not perceive reality[1] but instead generate it—and with this, the objects that we see as being real and concrete display more than just physical properties. They present themselves as meaningful and thanks to this, the accounts of our lives are replete with meaning.

Meaningful moments feed into meaningful narrative and that narrative motivates actions that expose us to new meaningful moments. This process–unlike more direct processes like emotions (which are often reduced to single cause-effect instances, to apparent success)–stretches out across time. To study meaning is to study an extended, dynamical process that unfolds over moments, minutes, hours, days, months, and years. For this reason–despite its ubiquitous presence in everyday conversation–meaning has largely been treated as an intractable subject for formalization. However, a shift from substance to process-based reasoning[2] has given us new tools with which we can examine formerly intractable tangles of complexity–in this instance, meaning.

We’ll first be discussing useful approaches to other phenomenologically complex concepts: the Theory of Constructed Emotion reimagines emotions as a constructive process and REBUS and the Anarchic Brain shows how phenomena and information can come together. We’ll then launch into an exploration of meaning dynamics, where we carve meaning into immediate and narrative senses and talk about how these interact with each other in a way that can be modeled and predicted.

The second part is an explanation of a pilot study we will be running. Here, we will cover current methods of studying meaning and identify peak experiences as being hotbeds of immediate and narrative meaning and construct an experiment from some reliable triggers of these experiences (psychedelics, flow, etc.). We will propose that the stimuli that accompany psychedelic experiences can themselves lead to entrainment and flow and, ultimately, peak experiences. Then, we will describe the pilot experiment and the resulting predictions, as well as the significance of each possible result. Last, we will discuss future directions to take this experimental design.

Emotions

Process-based line of thinking is increasingly represented in maturing theories. Feldman Barrett’s Theory of Constructed Emotion proposes the following:

In every waking moment, your brain uses past experience, organized as concepts, to guide your actions and give your sensations meaning. When the concepts involved are emotion concepts, your brain constructs instances of emotion. (Barrett, 2016)

Emotions are constructed as needed in the moment in order to help us maintain allostasis—relative stability in a complex environment. The traditional view is (roughly) this:

There exists some set of basic emotions: fear, anger, sadness, happiness. These basic emotions developed in order to provide our ancestors extra survival points. Fear feels the way it does because this feeling produces running away from the things we should fear. Sadness helps us socially bond and learn to avoid stimuli that could make us sad. Happiness steers us towards good actions like having kids. More complex emotions are combinations of essential emotions. Angst is two parts sadness and one part anger. These emotions are revealed through facial expressions and modular neuronal firings—fear is in the amygdala and anger the amygdala and hypothalamus. We also reveal our emotions through some set of behaviors. Sadness means tears and frowns, anger means red faces and balled fists. This is of course a caricatured version of the classic view, but it isn’t that far off. At its core, the classic view of emotions is that they are essential, common kinds and that they feel the way that they do because this feeling drives us to action.

The Theory of Constructed Emotion maintains the action-based conclusion—emotions must cause us to act in some way or they wouldn’t have emerged in the first place. However, we could easily imagine building a robot that behaved similarly to a human in the face of danger: If a dangerous object is present, then the emotion-free robot must activate its jet propulsion escape mechanism. Most would not be tempted to say the functional behavior that sometimes follows the onset of an emotion is itself the same as the emotion—though the traditional account has treated these things as being the same in practice. People who are experiencing fear sweat like scared people do, have increased cortisol levels, raise their eyebrows, and either run or fight or freeze up. This view turns out to be practical for designing experiments but also turns out to produce rather wild variation that is folded into the “noise” category. It also doesn’t get at the thing that matters most here, which is that emotions feel like something at all. The way these feelings manifest themselves over hours, weeks, days, and years are not practically measurable. Yet, for however impractical the feelings are, it is these feelings that shape the world as we experience it—not the facts that underlie these feelings.

The Theory of Constructed Emotion rightly recognizes the primacy of affect at play here. Instead of treating emotions as serving some high-level function (e.g., see snake, run from snake), it treats emotions as constructions. These are constructed from affect (i.e., how we feel), context, and prior learning—all to serve a single purpose—maintain allostasis (Barrett et al., 2016). This construction process is not describable in physics-friendly terms, except at the margins. Yet emotions are entirely central to our experiences as humans and therefore deserve our continued understanding and inquiry. Similarly, describing emotions in purely evolutionary terms does them a disservice. We’ve developed language and culture and have altered our environments such that new and complex emotions are now possible to express and share. And, more ambitiously, we could say that it’s possible to experience new emotions that our ancestors never could have experienced. Still, the fundamental pieces for emotions have been in place for quite some time—what are these?

Minimally, affect, environment, and an agent. Again, these aren’t physics-friendly pieces, but this doesn’t mean they can’t be examined and modeled.

Affect

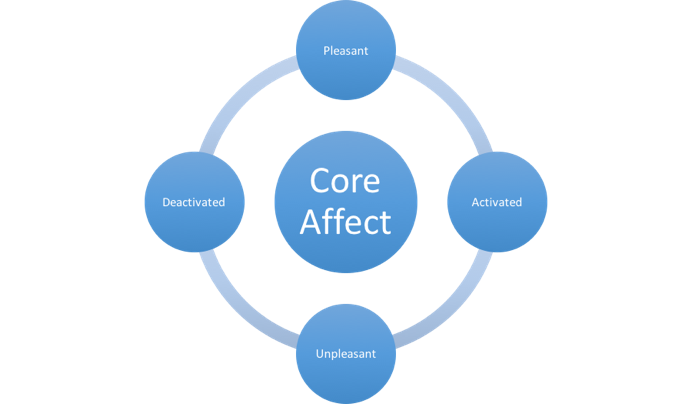

Though overly simplistic and incomplete, Russell and Barrett’s Core Affect provides a useful illustration of the dynamics underlying affect[3] (Russell & Barrett, 1999). According to Barrett, this affect is continuously accessed through interoception.

Figure 1 - Russell and Barrett's Core Affect processes

Environment

The environment is accessed through sensory modalities—and our continued survival seems to indicate that we are passingly decent at generating models of the environment and moving ourselves around it.

Other critical aspects of the environment are the language and culture that let us navigate its complex and changing parts. Language lets us communicate our own emotions and learn new and novel emotions, as well as help us continually calibrate these through learning.

Lastly, the environment is full of other minds, real or imagined.

Agent

In Barrett’s view, humans might be the only animals with full-bodied emotions, though it’s entirely possible other beings have just as much or more affect. This is because emotions—as she has outlined them—require language and cultural learnings.

An agent acts in accordance with its own goals (though this is often not in any obvious manner, modeling agents necessarily assumes that goal-achieving underlies the decisions agents make).

Allostasis

Underneath affect, environment, and agency, emotions have one last critical dimension—their ability to maintain allostasis—the energy and metabolism regulation at the core of emotions, their raison d'être. The reason we can interocept in the first place is because it gives us an interface into what’s going on inside our bodies, which lets us plan out and act in accordance with whatever will maintain allostasis. This view also rests on predictive processing, which posits that the brain is always generating and updating mental models of our environments.

Together, emotions are constructions of an agent in an environment, generated to maintain allostasis as a bottom line. While we don’t have to tie ourselves to all of Barrett’s claims or the claims underneath her claims, the allostatic approach is promising and may be useful for describing more than constructed emotions. Namely, we can borrow this triadic relationship and its dynamics: agent, environment, and goal.

REBUS and the Anarchic Brain

Carhart-Harris and Friston took a similar approach to bridging high and low-level phenomena in a very different space—psychedelics. Instead of focusing on metabolism and energy at the level of an organism, they modeled the apparent shifts in mental states between normal waking states and those experienced while under the influence of a psychedelic (e.g., psilocybin, LSD). They call this REBUS (Relaxed Beliefs Under Psychedelics, a tortured acronym):

…via their entropic effect on spontaneous cortical activity—psychedelics work to relax the precision of high-level priors or beliefs, thereby liberating bottom-up information flow, particularly via intrinsic sources such as the limbic system (R. L. Carhart-Harris & Friston, 2019).

Where Barrett’s view was about making predictions within an expansive and dynamic environment (i.e., the world that we live in), Carhart-Harris and Friston focus on even higher-level predictions (described as priors here), such as beliefs. Psychedelics relax the restraints on bottom-up information flow, allowing us to more directly interface with our sensory signals. Not only does this result in a subjectively interesting experience—where colors are brighter and sounds are more vibrant—but it also results in more enduring changes to “precision weighting of pathologically overweighted priors underpinning various expressions of mental illness”. In other words, the relaxation of priors directly and enduringly alters pathways that lead to mental health issues such as anxiety and depression, as an effect of their rigidity. This work ultimately rests on the demonstrated efficacy (Davis et al., 2020; Grob et al., 2011; Vermetten et al., 2020) of psychedelics in treating a variety of pathologies marked by their stubbornness.

From the physics and modeling-friendly perspective, the REBUS model also points to a particular kind of serotonin (5-HT2AR) as a driver of change:

The basic idea—pursued in this article—is that psychedelics act preferentially via stimulating 5-HT2ARs on deep pyramidal cells within the visual cortex as well as at higher levels of the cortical hierarchy. Deep-layer pyramidal neurons are thought to encode posterior expectations, priors, or beliefs. The resulting disinhibition or sensitization of these units lightens to precision of higher-level expectations so that (by implication of the model) they are more sensitive to ascending prediction errors (surprise/ascending information)… Computationally, this process corresponds to reducing the precision of higher-level prior beliefs and an implicit reduction in the curvature of the free-energy landscape that contains neuronal dynamics. Effectively, this can be thought of as a flattening of local minima, enabling neuronal dynamics to escape their basins of attraction and—when in flat minima—express long-range correlations and desynchronized activity.

At the neurophysiological level, 5-HT2ARs get agonized by the psychedelic, leading to hypersensitivity to context—this in turn presses the overall network to change itself (as part of minimizing free energy (Friston, 2009)). In terms of dynamics, agonizing 5-HT2ARs leads to desynchronization and greater reverberation, forming and fostering some connections and weakening and flattening others.

There’s a lot to this, but the most relevant to our interests is the idea of relatively small changes affecting widespread neurological change that manifests in changes to higher-level processes like personality and belief.

Weaving REBUS and the Theory of Constructed Emotions together, we might be able to start getting into what a theory of meaning dynamics might look like.

For one, it cannot afford to take an eliminativist or reductionist approach—the phenomena we care about exist in and of themselves, regardless of their neurophysiological underpinnings. Both discussed views (constructive emotions and REBUS) wrestle with high-level phenomena: emotions and complex pathologies. Yet they also stay rooted in both evolutionary and information theory. Emotions are ubiquitous and pervasive enough in our thoughts and words that it would be extremely surprising to discover they served no purpose or that they could have readily been replaced by more robust and simple-to-evolve functions—at least at the level of complexity we occupy. Psychedelics, while wild and great fun to discuss and explore, are also evidently capable of effecting long-term psychological transformation. Yet they cannot be reduced to simple panacea—we do not simply take them and cure our anxiety/depression/addiction/PTSD as though these were Brave New World’s soma[4]. Instead, taking them induced a particular kind of altered state that leads to widespread, enduring mental changes—seemingly dependent on set, setting, onset, peak, and post-peak experiences—all in addition to the short-lived changes to our 5-HT2ARs. A reductionist approach to this would greatly limit our insight (though reductionism in the space is still quite mainstream—there are multiple high-profile efforts to produce psychedelics with no apparent inducement of altered states).

When it comes to modeling meaning dynamics, we also cannot afford to further subdivide concepts. For example, it is often believed that happiness and meaning (in the meaning of life) sense are the same thing. Yet happiness smuggles in several non-useful assumptions: that life ought to be aspirationally good, that everyone wants to have as much of it as possible, that there is a unified account of it, and that its absence is itself unhappiness. Meaning in life need not make such assumptions. Like constructed emotions, meaning in life can instead bind itself to survival and flourishing, to relatively straightforward informational principles that use it to some ultimately valuable end. And like REBUS, meaning in life can describe a series of acute, contextually sensitive changes that lead to an overall change in dynamics that is at least a bit predictable—if we’re careful.

Meaning, fast and slow

Meaning—in the meaning of/in life sense—is a dynamical process. Across societies and cultures, we find a curious obsession with some ultimate sense of meaning. What is the meaning of life? The universe? My life? These questions are often taken to be rhetorical. Science—in its earnest solemnity—would of course respond that the universe and everything in it has no fundamental meaning. Everything that is and ever was is just the result of particles and patterns that have no intention. Meaning is a human-level construct. And this of course is a perfectly rational stance from a dispassionate, practical, logical perspective. Any meaning we examine and model must be understood to be relative to organisms on the order of human organization and complexity. As is the case with emotions, the further we stray from humans and the cognitive tools we wield, the less certain we should feel that our intuitions about the nature of consciousness apply.

There are at least two[5] different senses of meaning in life. One is the one we’ve been discussing here—the meaning in life sense, which I will call narrative meaning. This is the purpose or direction that we believe our life serves. In a way, this narrative meaning is an optimistic, self-fulfilling prophecy that shapes our day-to-day experiences. I get up and go to work not just because the work makes me feel good, but because I believe there’s some purpose in it. And while I do plenty of things that don’t directly contribute to my meaningful goals and dreams, it’s not that difficult to reframe most of my actions in terms of my ultimate (narrative) sense of meaning[6].

Narrative meaning

Narrative meaning is non-static. Its construction changes with changes to self, friends, age, culture, location, and so on. This shift is not often noticed, as it is subtle and taken as self-evident. What I care about is that which is worthy of being cared about—and if I stop caring about it, it must not be that important. This concept is expressed in Heidegger’s concept of authenticity, which attaches positive virtues to the pursuit of one’s meaning. To him, there’s a particular set of attributes that can lead one towards this authentic end—perseverance, integrity, clear-sightedness, flexibility, and openness—all of these and more are virtues that we can cultivate throughout life if we want to be as authentic as possible (Okrent, 1993).

This authenticity is a subtype of Heidegger’s conceptualization of care. We (Dasein) find ourselves in a world that matters to us. Our moods (or dispositions) shape the world we find ourselves in. This world is constructed from past (thrownness/disposedness), future (projection/understanding), and present (fallen-ness/fascination). Heidegger’s particular terms (roughly) break down as follows:

- Thrownness: the experience of finding yourself in a world that means something to you

- Projection: the culturally shaped possibilities that shape the way you inhabit the world

- Fallenness: how you actually find yourself living in the world[7]

These three aspects of care–past, future, and present–are a dynamic process. The way we experience the world as meaningful (thrownness) shapes our experiences of the possibilities (projection) available to us. In practice, we limit the scope of these possibilities (fallenness) and instead follow a narrow track of experience as we move through time and space. While Heidegger’s terms and explanations are far from straightforward, they at least demonstrate philosophy’s more formal interest in wrestling with the complex, dynamical, meaning-filled process that shapes human experience.

Returning to our conceptualization, narrative meaning is not a sterile essence but is instead a dynamic construction, similar to an emotion. What is it constructed from? In the case of emotions, these were affect and context, including language and culture. Narrative meaning is similar but not the same. It is highly language and culture sensitive. And it is sensitive to my interoceptive feelings at the moment of construction, but there’s also a memory and imagination-driven aspect. When I am asked to construct narrative meaning (e.g., explicitly, someone asks me what I’m doing living where I’m living), I take several things into account when constructing my response—without necessarily being aware of most of this process. I take stock of how things seem to be going. I also do a bit of comparison. Am I doing well according to how I think I should be doing? How have I been doing? How will I be doing once X happens? Of course, most of this is hidden from me and sometimes I will automatically respond without consideration (as most do when people ask “how are you doing?”). But somehow this question of meaning makes perfect sense no matter where or who or when I am—I can answer it sincerely because it is being asked and answered throughout my life, though it is not always easy to answer. In the case of severe depression, the answer that asserts itself is often some nihilistic claim, for me or for everyone: “Life has no purpose.” Or, “Life has nothing for me.” A declaration of the absence of meaning indicates an absence of something most people take for granted—immediate meaning.

It must also be noted that narrative meaning need not be limited to an actual narrative. We need not consciously or deliberately spell out the exact narrative by which we find ourselves living. This is similar to Heidegger’s projection aspect of care. And though we have used the word “belief” to describe our attachment to narrative meaning, the kind of belief we are demonstrating is not one with which we might identify, if pressed. If I say and experience genuine conviction that I am, say, an Effective Altruist[8] but this does not manifest itself in my behavior (e.g., I donate to the Red Cross[9]), then it’s clear that my beliefs are shallow. The kind of belief I am referring to in narrative meaning is–necessarily–authentic and aligned both with my experiences and intended actions. Therefore, intentionality is a more direct indication of narrative meaning than belief (which can effectively hold little to no relevant intention, apart from social signaling). Narrative meaning refers to the feelings and intentions that drive the construction of narrative–they are not the narrative itself. Narrative meaning is a process, not a substance.

Immediate meaning

Immediate meaning is meaning in the moment, meaning that is experienced directly by us, meaning that is reflexively attached and bound to the objects that surround us. My cat is not just an instance of felis catus—a small, predatory mammal that lives in the rectangles I live in that some Homo sapiens might call a “house”. I see my cat as special and unique. Seeing my cat is a different experience than seeing a different cat. Similarly, if I were to gift you a rock and tell you I got it in Scotland from a sheep farmer I met whilst traveling the highlands, you would find that rock more immediately meaningful than if I handed you a rock and told you it came from my backyard. The objects that surround us—in addition to having superficial features like shininess and color—have a wide array of other features. Some of these are captured in the concept of affordances, the “the quality or property of an object that defines its possible uses or makes clear how it can or should be used” (Gibson, 1969). We could say that the immediate meaning of a particular object can be reduced to its potential function. However, that’s not aligned with how meaning is experienced. It doesn’t feel as though the special warmth I feel towards my cat or the fraternal affinity you feel towards my Scottish rock are the mere experience of the functional features of each object. And this also doesn’t speak to the individual differences at the heart of these experiences. While it may be tempting to approach meaning in strictly immediately causal terms, doing so would fail to capture and explore the ways in which meaning dynamics express themselves over time. In fact, even the concept of an affordance only makes sense when we combine it with meaning.

If an affordance is “the quality or property of an object that defines its possible uses or makes clear how it can or should be used”, meaning immediately asserts itself:

- What is an object? Something that is perceived to be an object.

- How can an object be used? In a way that is useful to an agent.

- How should an object be used? In a way that affects an agent.

Experience can (presumably) be stripped from affordance as defined here. However, this version of affordance–where there is no experience–is stiff and brittle. The actions an object can perform are limited, the goals of the agent are constrained, and any change to the environment will require a shift in perception and use. Similar to how meaning in language is more than symbols and shapes, affordance is about more than objects and features–even if it does not appear this way at first. Affordances smuggle in intentionality as a matter of relevance. Objects only present themselves as having affordances in light of our having long-term narrative interest in them, and this long-term narrative interest in them is in part shaped by our immediate experiences of them. To us, the world is full of objects, and these objects all carry immediate meaning.

Awe

Immediate meaning, though difficult to examine abstractly, drives high-level behavior… or does it? Aside from affordances, is there a way to reduce immediate meaning to smaller parts? Perhaps. Much of what I have been describing as “immediate meaning” is lumped into the broader, nebulous category of emotion. For instance, Keltner et al. describe awe as an emotion that shares a striking number of similarities to immediate meaning.

To Keltner, awe is marked by two features: vastness, and need for _accommodation _(Keltner & Haidt, 2003). Awe is further flavored by five additional themes: threat, beauty, ability, virtue, and supernatural causality. These themes—when present—generate and shape the experience of awe. While it’s beyond the scope of our interests here to do a deep comparison to immediate meaning, we can still critically examine this particular awe concept.

First, it is problematic to consider awe to be an emotion, at least from the classic emotion view. Indeed, Keltner recognizes this: “One reason psychologists have devoted so little attention to awe may be that it has not yet been shown to have a distinctive facial expression.” Keltner avoids this concern by working around the edges. Searching for somewhere in psychology that awe has seen any representation, he finds Maslow’s 25 features of _peak experiences _(Maslow, 1964). Awe is among the emotions associated with these experiences, alongside wonder, reverence, humility, and surrender. Relevant to our interests, Maslow states that—during peak experiences—reality is perceived with “truth, goodness, beauty, wholeness, aliveness, uniqueness, perfection, completion, justice, simplicity, richness, effortlessness, playfulness, self-sufficiency”. These perceptual features are strikingly similar to those we would expect from immediately meaningful objects and relations.

While Keltner’s work on awe is comparable to what we’re doing here with immediate meaning, its attachment to emotion theory holds it back. Awe, among other oddball emotions, is not a great fit for mainstream emotion theory. This is partly because awe is (especially) difficult to track down in expressions and brain scans and partly because talking about awe requires an expanded set of conceptual tools and instruments. Awe cannot be meaningfully reduced to a change in galvanic skin response or a class of facial expressions, yet it is perfectly coherent to talk about in folk psychological terms. So too are both narrative and immediate senses of meaning. This was recognized by the continental/existential philosophical tradition, but these have mostly remained separated from the analytic philosophy-friendly mainstream work of psychology and neuroscience, which emphasizes subjects, objects, and objective truth as forming the basis of reality, with consciousness and chaos serving as annoying stumbling blocks.

Dynamics of meaning

I propose we think of immediate meaning and narrative meanings as a pair of highly interrelated processes that constitute an emergent, dynamic process of meaning generation. At the heart of this process are the agent (us) and the environment (constructed from learning and experience)–these interact in a particular way to generate goals and the desire to pursue them.

Immediate meaning

Immediate meaning—in the moment, apparent, reflexive, direct experience—is what we experience as we move around in the world[10]. Information flows into us through our sensory organs and internal processes. Part of processing this information flow involves attaching meaning to the objects and relationships we construct. Immediate meaning is therefore both experienced and learned, alongside our other learnings. It is experientially notable when we are exposed to something that doesn’t fit our mental models—otherwise, it goes unnoticed unless specifically attended to. Each instance of immediate meaning comes with different degrees of intensity and qualities. Leaning on Maslow’s description of peak experiences (what I consider to be experiences marked by their abundance of meaning), immediate meaning involves experiencing objects and relationships as having varying levels of “truth, goodness, beauty, wholeness, aliveness, uniqueness, perfection, completion, justice, simplicity, richness, effortlessness, playfulness, self-sufficiency” attached to them (Maslow, 1964). This also means that immediate meaning can be notably absent. Such absence is well-captured by placing the word “just” in front of a description of an object. My cat is “just” a cat and my mother is instead “just” my mother or—even more abstractly “just” a Homo sapiens that happened to have given birth to me, another Homo sapiens.

This concrete-to-abstract pulling apart is often encountered in depression. Where once I looked forward to eating my favorite dessert (banana cream pie), I no longer find myself caring about this “pile of empty calories”. Even more telling are the many disturbing accounts of schizophrenia that involve objects themselves being pulled apart into smaller abstractions:

For me, madness was definitely not a condition of illness; I did not believe that I was ill. It was rather a country, opposed to Reality, where reigned an implacable light, blinding, leaving no place for shadow; an immense space without boundary, limitless, flat; a mineral, lunar country, cold as the wastes of the North Pole. In this stretching emptiness, all is unchangeable, immobile, congealed, crystallised. Objects are stage trappings, placed here and there, geometric cubes without meaning.

People turn weirdly about, they make gestures, movements without sense; they are phantoms whirling on an infinite plain, crushed by the pitiless electric light. And I—I am lost in it, isolated, cold, stripped purposeless under the light (Sechehaye, 1951).

Here, not only are perceived objects stripped bare of their immediate meaning but so too are the behaviors of people impossible to fully comprehend without this meaning. Another account is as follows:

I perceived a statue, a figure of ice which smiled at me. And this smile, showing her white teeth, frightened me. For I saw the individual features of her face, separated from each other: the teeth, then the nose, then the cheeks, then one eye and the other (Sechehaye, 1951).

This person is described as the author’s closest friend and caretaker, yet the breaking apart of immediate meaning made a warm smile appear macabre.

These are of course extreme cases. More typically, objects gain and lose their immediate meaning with some subtlety. Everything we perceive carries some of this shifting meaning. What can cause this shift? Familiarity, for one—meaning is only notable when something has changed. Mood also alters this, as do fatigue, hunger, and stress. These all affect the overall experience of objects and their relationships.

Feelings of being

Ratcliffe presents a similar concept to ours–Feelings of being. While philosophers have argued that bodily feelings are unintentional (that is, not directed at or about anything), perceptions/expressions of bodily states, and consciously experienced (C. Solomon, 2004), Ratcliffe presents a more process-oriented view (Ratcliffe, 2005):

(1) Bodily feelings are part of the structure of intentionality. They contribute to how one’s body and or aspects of the world are experienced._

(2) There is a distinction between the location of a feeling and what that feeling is of. A feeling can be in the body but of something outside the body. One is not always aware of the body, even though that is where the feeling occurs.

(3) A bodily feeling need not be an object of consciousness. Feelings are often that through which one is conscious of something else.

Immediate meaning shares these attributes–it is about both the world and the body, often goes unattended, and shapes the experience of the objects and relationships we have. This similarity ought not to be surprising: immediate meaning is a feeling of being–the difference is merely an emphasis on understanding how immediate meaning interacts with narrative meaning. This means that most of what Ratcliffe argues for in The Feeling of Being and related work applies here, particularly his arguments regarding pathological alterations to these feelings in depression, anxiety, Cotard delusion, Capgras syndrome, and schizophrenia. Roughly, the central claim is this: a breakdown in feelings of being (where immediate meaning is understood to be an aspect of these) leads to and exacerbates the development of these pathologies.

Meaning and the fringe

Another line of thinking is found in Mangan’s work on consciousness, fringe, and aesthetics. In this, Mangan brings together William James’s conceptualization of consciousness and combines it with meaning–tied strongly to the sense in which objects appear to us as being meaningful beyond the sum of their parts. Here, consciousness is described as having a two part structure: “One part consists of distinct contents, the other of vague and peripheral experiences or feelings. Meaningfulness only lives in the

second, vague aspect of consciousness” (B. B. Mangan, 1991). The first part is what James referred to (among other things–he was poetic) as the nucleus, the center of experience (B. Mangan, 2007). This is described as what we perceive with our senses–a high-resolution stream of information with definite features and feelings attached to it. The second part is called the “fringe”. The fringe consists of the indefinite and peripheral, supporting the nucleus. Mangan describes this as “context”. Our experiences (while awake and aware) have a central and definite and clear quality, but indefinite context undergirds each of them. Such context is noticed in its absence and is subsumed by the focus in its presence. Meaningfulness, as a denizen of the fringe, is therefore subject to augmentation and attenuation. Moreover, fringe contents have an additional property of being partially available to more direct and distinct attention in the consciousness-accessible nucleus. Meaningfulness is therefore implied to be directly accessible through thought.

Are Mangan’s Meaningfulness and our immediate meaning the same? Yes, roughly. Though–as was with the case with Ratcliffe–our emphasis is on the dynamics between narrative and immediate meaning. Mangan’s Meaningfulness is conceptualized as a fit to James’s nucleus-fringe framework. To wit, Mangan says this of Meaningfulness (B. B. Mangan, 1991):

…all of Meaningfulness' functions are applications of a single function: to signal context-fit. At base, Meaningfulness signals nothing except the degree of coherence or compatibility between a given content in consciousness and its appropriate nonconscious context.

This is a strong statement–Meaningfulness only serves one goal: context-fitting. And the experiential richness of Meaningfulness is described as a single thing: a signal[11].

These strong claims lead to another one: “..._to maximize Meaningfulness in consciousness is to increase the integration of conscious and nonconscious information”. _Therefore, Meaningfulness can be modulated by increasing the integration of the nucleus and fringe aspects of consciousness. In principle, as long as we can feel empirically comfortable with current tools that purport to study meaning (such as the Meaning in Life Questionnaire), we ought to be able to test this claim. Can Meaningfulness be increased by integrating conscious and nonconscious information? Yes, assuming we can develop an instrument that integrates this information.

Narrative meaning

What is demanded of man is not, as some existential philosophers teach, to endure the meaninglessness of life, but rather to bear his incapacity to grasp its unconditional meaningfulness in rational terms (Frankl, 1962).

Narrative meaning is the goals that drive our behavior at a high level. Though it is ultimately adaptive—narrative meaning leads to action that allows for survival, reproduction, and flourishing—it ought not to be reduced to its utility. While an outside observer might say my lifelong passion for tennis is just a manifestation of my desire for friends and exercise, I certainly do not experience it that way. Frankl, an influential existentialist, agrees: “Confounding the dignity of man with mere usefulness arises from conceptual confusion that in turn may be traced back to the contemporary nihilism transmitted on many an academic campus and many an analytical couch” (Frankl, 1962).

Narrative meaning is not a single ultimate goal but is instead a shifting constellation of goals that interact with each other and change as our environments change. And though we don’t always do this directly, it is perfectly coherent to ask anyone in any culture in any language what they want out of life. When I get up in the morning, I don’t just do it because I can’t sleep anymore or because I feel the need to forage for food—I do it because I need to do it in order to do something else. And when asked about, I can provide an earnest account of my underlying motivations.

Narrative meaning changes across time and situation. For example, we find that conservative beliefs (themselves laden with meaning statements such as “family is the most important thing in the world”) are somewhat predictable at scale, given population density and availability of resources (“Can Population Density Predict Voting Preference?,” 2015). Yet, there is a great deal of variation within these patterns. The context with which Frankl observed meaning and suffering in Man’s Search for Meaning was as a Holocaust captive. Here he considered and contrasted the varying ways with which others dealt with their horrible situation:

Dostoevsky said once, "There is only one thing I dread: not to be worthy of my sufferings." These words frequently came to my mind after I became acquainted with those martyrs whose behavior in camp, whose suffering and death, bore witness to the fact that the last inner freedom cannot be lost. It can be said that they were worthy of the their sufferings; the way they bore their suffering was a genuine inner achievement. It is this spiritual freedom—which cannot be taken away—that makes life meaningful and purposeful (Frankl, 1962).

This hints that there may be dispositional and/or strategic ways of constructing narrative meaning, regardless of environmental particulars. If an abundance of narrative meaning is dispositional, it could be that some are simply more or less inclined to reflect in this way. And if narrative meaning is strategic, it can be understood and learned. Both ideas hold water. Frankl seems to have believed the same. As a result of his experiences and learnings, Frankl established a line of psychotherapy entitled “logotherapy”—literally, logic-based therapy. The hope was that logotherapists could help walk their patients through a process of using logic to reframe semantically similar events. For example, if my old dog (Fido) dies and I’m beside myself with grief, asking myself “why me?” or “why Fido?” questions, logotherapy would ask me to think about how this event could be used for reflection and understanding. I might instead think “Fido had a great life—he wasn’t able to do most of what he enjoyed in the end, but I’m glad we were able to spend this time together”. This is (equally) technically true and more importantly, pragmatic. Someone who has learned to generate effective-yet-honest reframings will be able to handle adverse events much better than those who cannot—or so logotherapy claims. Regarding narrative meaning, logotherapy seems like one of potentially many tools to help alter the narrative.

Narrative meaning requires access to language and culture—without these, it is not possible to carry the kind of complex, long-term goal-driven information that is required. This claim is similar to Barrett’s non-intuitive constructed emotions theory claim: non-human animals do not have emotions, on account of their lack of complex language and culture. That isn’t to say that experience is exclusive to humans, but that meaningful experience is greatly limited in other animals, as it is missing a narrative aspect. In our framing, non-human animals may be able to have a flavor of immediate meaning and goal-driven behavior, but this would be simpler and lack some of the qualitative features human meaning has.

Combining immediate and narrative meaning

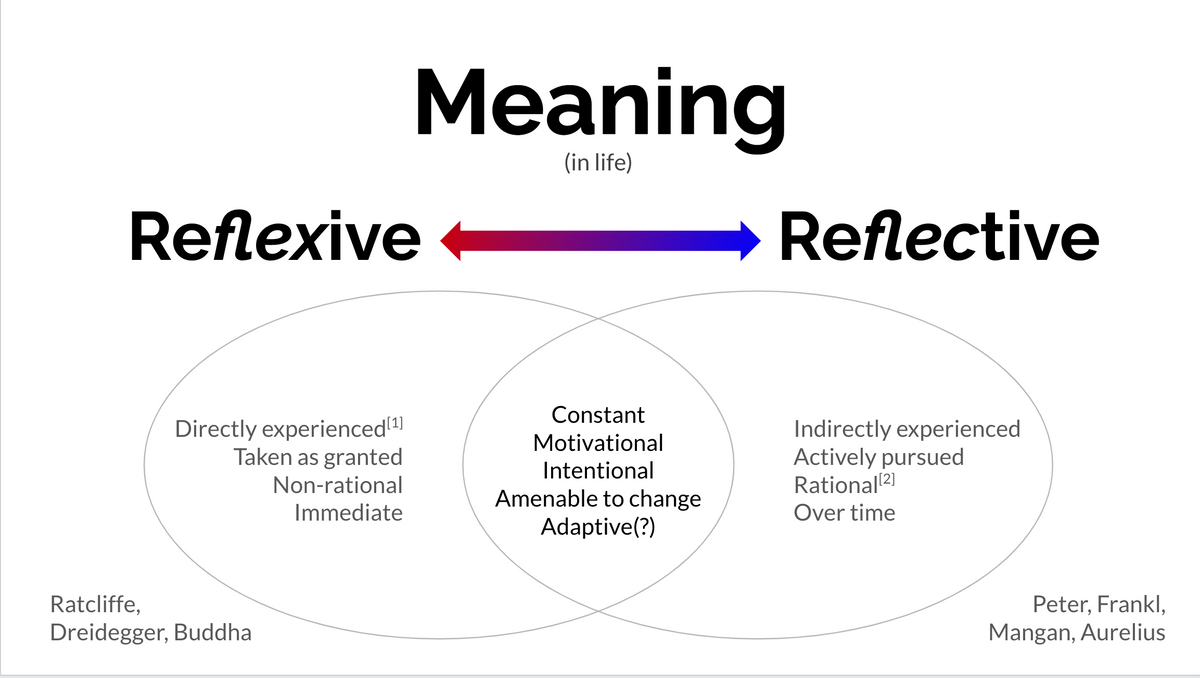

Figure 2 - Direct comparison of the two meaning processes

The central thesis here is that immediate and narrative senses of meaning are interdependent in humans and that their interactions are–in principle–predictable and controllable with adequate understanding. Both senses of meaning are central to our lives, yet this has not led to a formal line of research exploring their dynamics. How does a chronic absence of immediately meaningful experience lead to a change in meaning in life narrative meaning? How strongly can changes to narrative affect immediate experience? The answers to these questions will only be found once we commit to asking them, without reducing them to insubstantial proxies[12].

Let’s explore some surface-level dynamics: immediate meaning is affected by mood, familiarity, hunger, and stress, but it is more widely affected by shifts to narrative meaning. Narrative meaning is constructed from immediate meaning. Without immediate meaning, there could be no narrative meaning. The reverse is not true. Immediate meaning does not require narrative. However, without narrative meaning, immediate meaning would be far less dynamic and reaching in its behavioral outputs. Indirect evidence for this is found in non-human animals. These appear to have kinds of experience above and beyond the most literal kind—non-human animals show strong preferences for the friendly and familiar. While we unfortunately cannot verify this directly[13], if we think that the ubiquitous way in which humans perceive a world full of immediately meaningful objects is adaptive, it would be surprising if non-human animals were devoid of immediately meaningful experience. This argument might be thought to apply to the narrative sense of meaning. Long-term goal-attainment can be helped through narrative meaning. But this requires the powers of language and culture. Non-human animals do of course show signs of having long-term goals (e.g., squirrels hiding acorns, beavers building housing), but these are extremely stubborn and brittle and limited to just a few per species, even the cleverest ones. The dynamic flexibility—both with regard to task and time—requires the high-level abstraction afforded us by language and culture.

Briefly, then, immediate meaning is affected by various factors but can shift strongly as narrative meaning shifts. Narrative meaning is much more sensitive to immediate meaning. For us to feel like our life has purpose, it is necessary that this life—through memory and experience—furnish immediately meaningful instances. The statement “my life has meaning” only makes sense if this statement is made by a person who has had/can have immediately meaningful experiences. Though individuals who are undergoing difficult circumstances might be able to “see the silver lining”, this often feels unnatural, even forced. Recall the schizophrenia accounts: “Objects are stage trappings, placed here and there, geometric cubes without meaning” and “People turn weirdly about, they make gestures, movements without sense”. A world where this is the norm would almost certainly fail to provide the conditions necessary for producing narrative meaning. This can in part account for why people with severe depression—marked by in-the-moment apathy and disconnection, indications of lost immediate meaning—tend to produce nihilistic statements about narrative meaning: “Life has no purpose”, “What’s the point of living?”, and “Nobody wants me here”. These statements are typical of severe depression and reveal the strong connection between immediate and narrative meaning. Without directly meaningful experience, we cannot readily produce meaningful narrative.

Going in the other direction, we find that there’s still some connection between the two senses of meaning but that their relationship is different. If I believe my purpose is to be a baker and this leads me to take actions to become one, these actions could well lead me to immediately meaningful experiences. In a way, this is a self-fulfilling prophecy. I think that I want something and that shapes my experience of working towards that thing—each step feels especially meaningful insofar as I know it aligns with my narrative ends. (This echoes Heidegger’s care concept.) Of course, I might find along the way that I don’t actually enjoy the work of being a baker as much as I enjoyed the idea of being a baker. This separation of narrative and immediate meaning can lead to existential concerns. If I build my identity around the achievement of some goal and find the steps along the way onerous, then this can be, at minimal, genuinely concerning. At worst, it can trigger an existential crisis—or even lead to depression. It seems, then, that trying to keep the dynamics between immediate and narrative meanings healthy will involve efforts to keep the two in relative harmony. If I aspire to be something I actually have a hope of being (scientist, good father, monk) instead of something I will almost certainly never be (US President, prima ballerina, Pope), I might be able to avoid the backlash as reality crashes against immediate meaning. Just as importantly, aspiring to be something I can be is more likely to lead me to immediately aligned experiences. The journey matters just as much as the destination–though an absence of destination (built through narrative meaning) will constrain the range of possible experience. Goal-driven narrative compels us to change our situation, which in turn enables the generation of immediately meaningful experience.

We find many examples of this dual-aspect meaning process in religion, though Eastern and Western emphasis usually leads to favoring one over the other. In Christian circles, the emphasis is often on narrative meaning, spelled out explicitly in terms of ultimate purpose or meaning: “And this is eternal life, that they know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent” (John 17:3). There’s some care for individual experiences—sin only makes sense if we treat it as something that accumulates over time—but most modern Christian sects place stronger emphasis on long-term goals. In Buddhist circles, meaning comes from learning to overcome our desires. While there is an ultimate goal—enlightenment—this is attained through focus on overcoming and managing each moment. The dedication to managing individual experience is manifest in meditative practices that follow Buddhism, which teach practitioners to actively pull themselves away from narrative meaning in favor of intentionally focusing on the experience of each moment. Still, all persistent religions deal with both senses of meaning as a matter of fundamental doctrine and practice.

Another place to notice meaning is in the previously mentioned peak experiences described by Maslow and others. Some events seem to trigger altered states that are marked by their meaningfulness, both in the moment and upon reflection. In terms of behavior, these are recognized by the following symptoms (Maslow, 1964):

- Loss of judgment to time and space

- The feeling of being one whole and harmonious self, free of dissociation or inner conflict

- The feeling of using all capacities and capabilities at their highest potential, or being "fully functioning"

- Functioning effortlessly and easily without strain or struggle

- Feeling completely responsible for perceptions and behavior. Use of self-determination to becoming stronger, more single-minded, and fully volitional

- Being without inhibition, fear, doubt, and self-criticism

- Spontaneity, expressiveness, and naturally flowing behavior that is not constrained by conformity

- A free mind that is flexible and open to creative thoughts and ideas

- Complete mindfulness of the present moment without influence of past or expected future experiences

- A physical feeling of warmth, along with a sensation of pleasant vibrations emanating from the heart area outward into the limbs

Though a bit conceptually squishy, this description of peak experience ought to look familiar with regard to our conceptualization of meaning. More strongly, we say that peak experiences are meaningful experiences, both immediately and narratively speaking. If this is true, a careful examination of peak experiences could lead to us understanding the dynamics of meaning.

Self and meaning

We mentioned that meaning has intentionality–both senses of meaning have an aboutness. Immediate meaning is our feelings in the world, of the world (including our own body). It is also–per Mangan–a signal of context fit. Both of these framings hold us as a singular, uniform organism at the center and that which is immediately meaningful is meaningful in light of there being a single entity (us) that cares about its fate. This caring manifests itself subtly most of the time. When I feel tired, I don’t have to think that the feeling of being tired is directed towards anything in particular–both “I am tired” and the “feeling of being tired” blend together. This mostly goes unnoticed. Though I–a complex organism–am driven by allostasis, this low-level goal does not surface itself directly. I can reason about my feelings (why do I feel tired?) and supply narrative around this feeling (because I am hungry), but a True answer to this will always elude me. The “I” at the center of this approximation through narrative is my self. There are philosophies that deny the fundamental reality of an “I” at the center of experience, but experience only can be made sense of if there is an experiencer at the center of it. Feelings in the world can be made sense of when I believe that they are real and undeniable–to question my own experiences would be to question the only tools with which I have a hope of interacting with the world–my senses and my knowledge.

Both immediate and narrative meaning make use of the self (i.e., the implicit “I”). Immediate meaning needs the self to form the Jamesian nucleus to consciousness. Reality unfolds in a smooth, continuous, and coherent fashion around a center.[14] This is of course almost completely transparent to the experiencer. When I am hungry, I simply experience hunger and know that it is me who is hungry. Or at least I can assume it is me who is hungry–it is (perhaps) surprisingly straightforward to fool us into having an experience on behalf of other people, animals, or even objects[15]. Our self can readily blend into other apparent selves (Safdari Sharabiani, 2021).

Narrative meaning–unlike immediate meaning–has the self in the foreground. I care about my life and the lives of those who I care about. Even altruistic narratives have a self at the center. I want to help the less fortunate. This wanting may not come from my belief that it will benefit me in any way, but I could not want any particular outcome unless I identify as a human that could have such desires. This tension has concerned theologians of all backgrounds (“can one be truly good?”, “can one cast off all desires?”). But, as a matter of definitional coherence, narrative meaning necessarily entails a desiring, goal-driven self.

Given the presence of self in both immediate and narrative meanings, understanding the dynamics between them ought to entail a study and consideration of the self and the roles it plays.

Environment

Environment shapes immediate and narrative meaning just as much as they shape each other. The environment includes dynamically changing language and culture. The construction of meaning rests on the assumed existence and connection between our self and the other selves, real or imagined[16].

The thing that’s most constant is change–environment is that which produces changes to immediate meaning and shapes the development of narrative meaning. Another thing to note is that the existence and reality of other selves is secondary to the force they exert on our self. We are deeply social, leading our relationships to drive our narratives. Every narrative meaning can be straightforwardly reframed as a social narrative. Even if I (as a friend of mine does) find solving Rubix cubes as quickly as possible deeply enjoyable, I would still find myself comparing my score to others so involved. And even if no one were left besides me, I would still find myself comparing my current self with a memory of my past self or a projection of a potential self who is better than I currently am. The social narrative is flexible and accommodating. While we often try to distill human motivation into simple and straightforward factors (wealth, health, sex, etc.), the level of narrative that we live in is far more complex and variegated than these reductions.

It’s worth noting again that the narrative I give in response to a question of narrative meaning (e.g., “why do you solve Rubix cubes?”) is not, logically speaking, True. That is, when I give you any account as to why I did anything, this should be considered an assertion of belief, not truth. This belief should also be understood to be a snapshot at best–a small change to my mind or the environment can result in a different narrative response. Whatever I think of in response to the question will be constructed in the moment and expressed in imperfect language and therefore non-identical with some “objectively true” statement of meaning. Any explicit narrative we provide should instead be understood to be an informative construction. It gives indirect hints (to me and to everyone else) as to what is driving my behavior at a high level. Narrative meaning is dynamic and changing. This isn’t to say that it is useless–it’s still informative and still helps us make predictions about experience and behavior.

When I say my life is meaningful, I tell you something different then when I say my life has no meaning. And you learn something different when I struggle to answer the question at all. Narrative meaning is therefore best understood in context. Can the narrative be generated? How strongly do I feel that my life has meaning? Do other lives have meaning? Moreover, we can still investigate behavioral proxies. Do I hesitate and shift my eyes around when asked about meaning? Does my heart rate rise? Is my amygdala excited? We can even imagine tracking other related metrics–does someone who reports high meaning in life find arbitrary connections between things easier to form? Are people high in religiosity more likely to attribute intentionality to the arbitrary placement of wooden blocks[17]? There are myriad methods with which we can investigate meaning and environment once we commit to trying to investigate meaning for its own sake.

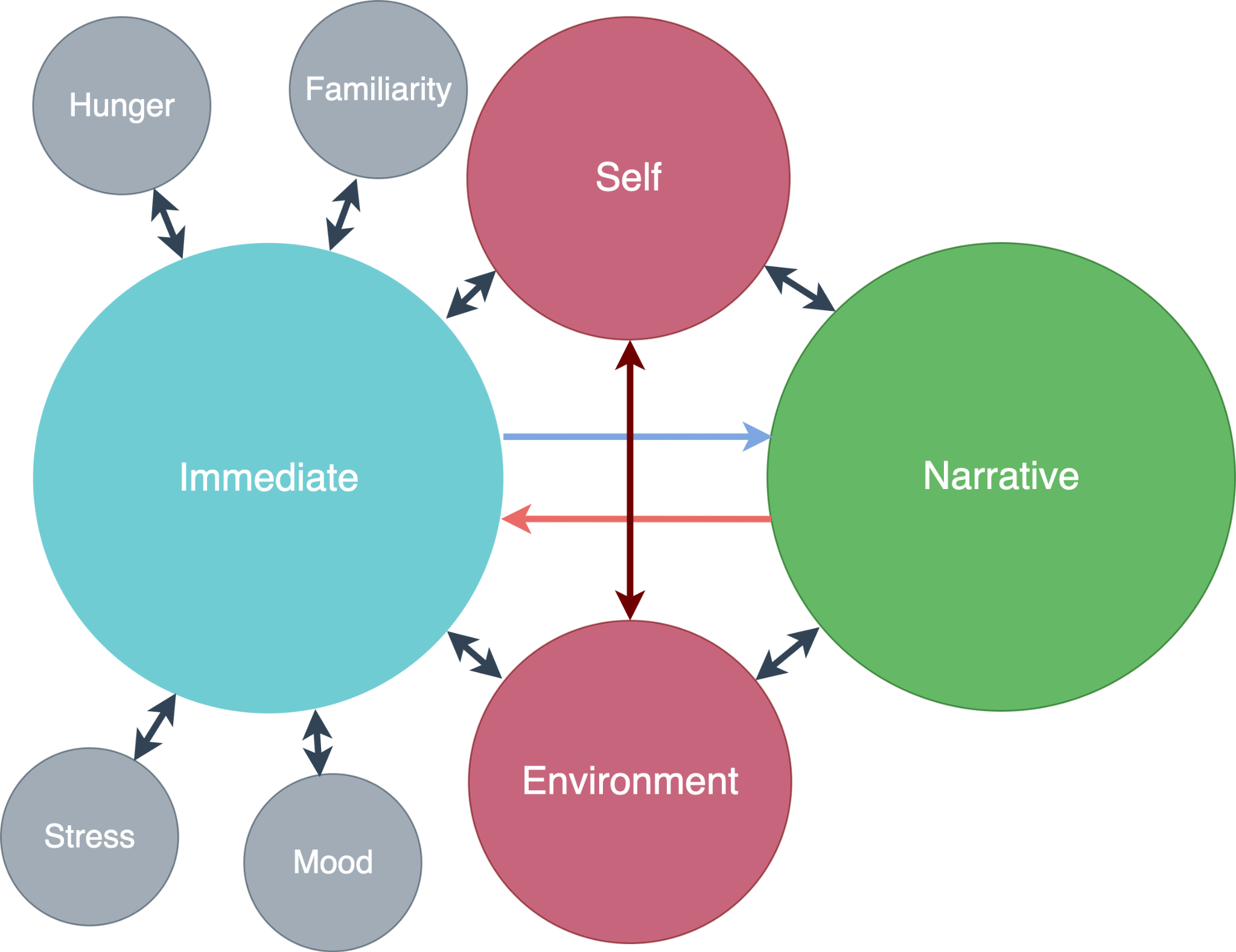

Figure 3 - Meaning dynamics - Immediate meaning gives context to narrative meaning; narrative meaning alters the environment and gives a backdrop for immediate meaning, which is additionally influenced by a variety of contextual factors. Self is shaped by the environment and leads to changes in the environment.

Modeling meaning

Now that we’ve discussed the aspects and relationships of meaning, we can more formally describe our proposed model.

On one side, we have immediate meaning:

- Reflexive experience of objects and relations between objects as being meaningful.

- The integration of conscious and nonconscious information

- Constructed from sensory organs and internal processes

- Learned (much in the same way as we learn to identify the physical properties and affordances of the objects in our world)

- Made attentionally salient through changes to information integration

- Accompanied by phenomenological properties (meaningful objects feel true, good, beautiful, whole, alive, unique, perfect, complete, just, simple, and rich)

- Affected by mood, fatigue, hunger, and stress

- Undergirded by self and intentionality

- Greatly impacted by narrative meaning

On the other side, we have narrative meaning:

- Purposeful, goal-driven thoughts and behavior over potentially long periods of time, throughout complex, shifting environments.

- Constructed through language and cultural cues, as well as memories and immediately meaningful experiences.

- Dependent on the development of language and culture (non-human animals do not have it[18])

- Motivational—narrative meaning drives our actions

- Notable in its abundance or absence

- Self at the center of most constructions (and still present in all other constructions)

- Construction depends on memories or experiences of immediate meaning (there can be no narrative meaning without immediate meaning).

The relationship between the two meanings is as follows:

- Immediate meaning is shaped by narrative meaning

- As our environment changes, so too does our narrative meaning, which in turn leads to shifts to our immediate meaning.

- Changes to our self changes both our immediate and narrative appraisals, both directly and through downstream effects these exert on our environment.

- An absence or abundance of immediate feedback adjusts narrative meaning

This process often goes unnoticed but can be observed as the dynamics shift. In some pathologies—namely, depression and schizophrenia—the inability to close the meaning loop manifests itself in experientially and behaviorally deleterious ways. On the other end, peak experiences describe an especially strong meaning dynamic, where conscious and nonconscious information blend together and lead to (potentially) long-term shifts to narrative meaning.

This is the rough model—testing and refining it is something else entirely. As depression and peak experiences are relatively accessible, we might look at them as pragmatic guides to understanding meaning.

The second part will be a discussion of Pivotal Mental States and peak experiences. We are using our understanding of these to design a series of experiments on measuring meaning in the face of stimuli meant to gently induce peak experiences. I will describe the pilot experiment in detail, as well as some promising directions we can take richer versions of the experimental setting.

Part 2: Experimentation

Current methods of quantifying meaning

Meaning in life research has a limited experimental background. Between psychology and anthropology, the current gold standard is to wield one of several questionnaires[19] designed to capture meaning–particularly, narrative meaning[20]. Ward and King (2016) ran three studies that used the Meaning in Life Questionnaire to see how reported meaning interacts with income and positive affect. This questionnaire has 10 questions that ask respondents to rate how well each statement applies to them–these include “I understand my life has meaning” and “I am searching for meaning in my life”. Ward and King found the following:

- Those with high positive affect reported similar meaning in life, regardless of income

- Those with low positive affect reported higher meaning in life with higher income

- Without affect manipulation, higher income correlated with higher meaning in life (but this went away once affect was manipulated

- When asked to imagine how meaningful they would find their lives in the future, the wealthy projected having more meaning in life than the poor (where the most unhappy were the most poor)

A few small lessons can be learned from this and other similar studies. For one, this supports the assumption that mood plays an outsized role in the construction of narrative meaning instances. Another lesson is that environment helps form the background of these appraisals. The wealthy–without overt manipulation–reported more meaning in life, on average. An unspoken lesson is also found in the dataset: these kinds of high-level, large samples are replete with exceptions: there were many poor who had lives brimming with meaning and many wealthy with low meaning. Such variation should not escape our notice–if there are other mediating factors that do not show up with large, clinical sampling methods, we ought to investigate them.

Reflect on people in your own life with similar backgrounds–would you expect that they’d all score similarly to each other when posed these questions? You would not–there’s more to meaning than background and affect. Nor would we expect to score the same throughout our own lives. These variations and shifts are what most interest us here. Like the affect manipulation Ward and King used, we can hope to perform similar manipulations. But we need not stop there–if what we value is maximizing meaning, we ought to target an average increase to meaning in life over time. Even better, we should see whether this increase can sustain itself over longer periods of time.

Such an endeavor might require the development of new tools for exploring meaning dynamics and inducing long-term changes. These tools need not be developed in tandem but doing so allows us to cover more ground than if we focused on one over the other. Measuring meaning dynamics can benefit from stickier changes to meaning. Similarly, enduring changes to meaning can benefit from ways to measure and track these changes.

Before moving on, we should ask ourselves whether this work has been done (presumably well) by others. We already referenced Keltner and Haidt’s work (Keltner & Haidt, 2003) on awe, which has inspired a plethora of offshoots, from ethics to altered states to mindfulness (Liu et al., 2022; Thompson, 2022; Villar et al., 2022). These are interesting in that they do reference the kinds of peak experiences (Maslow, 1964) that we described as being highly meaningful, even formative. Such apotheosis experiences often lead to enduring changes in both narrative and immediate meaning (described qualitatively). An inquiry into peak experiences might therefore yield a fitting set of experimental goals that could lead to experiments that begin to explore and uncover meaning dynamics.

Meaning and psychedelics

Elsewhere, meaning in life has been examined in relation to psychedelics. Griffiths et al. (2006) administered psilocybin to volunteers in two to three sessions and asked them to rate the resulting personal meaning: “67% of the volunteers rated the experience with psilocybin to be either the single most meaningful experience of his or her life or among the top five most meaningful experiences of his or her life”. Further, “...volunteers judged the meaningfulness of the experience to be similar, for example, to the birth of a first child or death of a parent”. Such a result is striking–not just because it speaks strongly of the powers of psychedelics that they are vaunted like this–but also because it demonstrates just how strongly particularly powerful specific immediate experiences of meaning can be.

The study continues: “In written comments about their answers, the volunteers often described aspects of the experience related to a sense of unity without content (pure consciousness) and/or unity of all things”. These claims of contentlessness and unity speak to Mangan’s view on nucleus and fringe. Recall that he asserted the following: “...to maximize Meaningfulness in consciousness is to increase the integration of conscious and nonconscious information” (B. B. Mangan, 1991)_. _If Mangan is correct, maximally (immediately) meaningful experiences will be remarkably unified. The statement of content-free consciousness is also interesting. We claimed earlier that immediate meaning often goes unnoticed and that it is only when it is abundant or absent that we are compelled to attend to it. Combining this with Mangan’s view, we encounter a strange dynamic: the strongest immediate meaning is found when attention is made its strongest but then is transformed in the integration of conscious and nonconscious information. We attend strongly, then we merge the nucleus with the fringe, producing a different kind of attention[21].** **If this is true, then another tool for investigating meaning might be to focus on attention and inattention.

From Griffiths, we also get a hint that the exact content of peak (immediately meaningful) experience is not as important as the persistence of unity during and after the peak. If we deliberately pursue peak experiences, our focus should be on unity and that which comes with it:

- Flow: Complete absorption in one’s activity (Ellis et al., 1994)

- Loss of self as center: Separation or blurring of the experience between the mind and body[22]

- Silencing of narrative: Dissolution of the narrative that often occupies our conscious experience

- Connection:** **Experience of self-other and other-other as forming a unified whole

This list differs from Keltner and Haidt’s appraisals central to awe: “...perceived vastness, and a need for accommodation, defined as an inability to assimilate an experience into current mental structures” (Keltner & Haidt, 2003). Perceived vastness and need for accommodation can lead to connection, a silencing of narrative, and a loss of self–in that sense, we’re talking about something similar. The difference is that Keltner and Haidt are mixing the cause with the effect (perception of vastness → awe, need for accommodation → awe), where we are not doing so explicitly. However, we will assert something similar: increasing flow, loss of self, narrative silencing, and/or connection directly leads to immediately meaningful experiences. These factors further lead to changes to narrative meaning (since narrative meaning is constructed from immediate meaning). Though tools such as the Meaning in Life Questionnaire are rough and limited, they present a potential way to quantitatively measure the effects of altering the above factors. In short, by investigating alterations to flow, self, narrative, and connection, we might be able to use more mainstream measurement tools to tie narrative meaning to immediate meaning.

Pivotal Mental States

Elsewhere, we find work to tie meaningful instances to a unified set of stimuli. A Pivotal Mental State (PiMS) is a “hyper-plastic state aiding rapid and deep learning that can mediate psychological transformation” (Brouwer & Carhart-Harris, 2020). This state is described in terms of evolutionary function and is tethered to a proposed set of neural correlates that could (in principle) predict whether someone is in a PiMS. According to the PiMS construct, chronic and acute stress trigger an altered state that is marked by its enduring downstream effects.

“Stress” is defined here as “the body’s multi-system response to any challenge that overwhelms, or is judged likely to overwhelm, selective homeostatic response mechanisms” (Day, 2005). The emphasis on homeostasis echoes Barrett’s Theory of Constructed Emotion, where emotion is said to have developed as a way of maintaining homeostasis in a complex social world. So too are PiMSes proposed to be a natural response to the world changing, albeit in a more extreme way. The stress a soldier on the battlefield undergoes–chronically and acutely–leads to a pivotal state that forces the body to make large adjustments. On an information level, this involves enduring changes to learned priors. PTSD is therefore given to be the result of extreme environmental changes leading to a singular episode of strong rewiring. Such events are highly meaningful–changes to the system that produces immediate meaning manifest themselves in narrative meaning. For better or for worse, to someone who has served on a battlefield, the experience of doing so plays an outsized role in the remainder of that person’s life.

Brouwer and Carhart-Harris’s paper is mostly centered around considering psychedelics as an acute PiMS trigger. These are near-direct triggers: you merely provide some context (set) and the trigger (psychedelics altering 5-HT2AR serotonin receptors), resulting in a pivotal state.

PiMS presents a potential inroad to studying meaning dynamics. The exact stressor is not important so much as its properties and its downstream effects. In other words, we can invent our own PiMS trigger based on PiMS principles and expect to see similarly meaningful outcomes.

What should these triggers look like? Brouwer and Carhart-Harris define stress as a general bodily response to overwhelming challenge, but this is not specific enough to be actionable. They also name candidate triggers: psychedelics, life-or-death situations, meditation, and breathwork. Besides inducing PiMS, what is common among these? They all heavily involve aspects of peak experiences: flow, loss of self as center, silencing of narrative, and connection. Put straightly, instances of PiMS are peak experiences and PiMS (as a construct) endeavors to give an evolutionary account and to bind experience to neural and informational correlates.

Generating peak experience

Can we intentionally generate peak experiences in order to induce immediate meaning and shape narrative meaning? If the Pivotal Mental States construct holds water, the exact mechanism for generating peak experience is less important than its proximate and downstream effects. If we take psychedelics as a core example of successful peak experience production, we can lean on typical aspects of the psychedelic experience to generate mental states high in immediate meaning, integrating conscious and nonconscious information, per Mangan (1991). How do we integrate conscious and nonconscious information? By intentionally copying aspects of the psychedelic experience.

“Psychedelic” means (literally) “mind-revealing”, implying that psychedelics are revealing our own minds to our selves. This contrasts itself with the experiences themselves, which involve hallucinations and illusions of a wide variety of shapes, patterns, sounds, smells, tastes, and tactile events, as a matter of fact–all amounting to a peculiar kind of altered state. Further, the altered state is replete with meaning and the aspects of peak experiences we enumerated: flow, loss of self as center, silencing of narrative, and connection.

Our central experimental thesis is this: targeting sensory and/or qualities of peak experience (flow, etc.) will increase immediate meaning. Moreover, combining multiple meaning-increasing stimuli will have an additive effect, which, at some point, produces long-term changes to both immediate and narrative meaning.

The assertion that sensory and peak experience correlates can themselves produce usefully altered states runs counter to our understanding–we treat these correlates as side-effects resulting from psychedelics messing with our neurons:

(psychedelics → altered states + correlates of altered states)

versus

(correlates of altered states → altered states)

For example, listening to specific kinds of music–live, loud, lyrical–readily produces a compelling experience. Without this experiential feedback, music would not be interesting to us, lacking useful information. Music does not hold any intrinsic meaning[23], yet we swear by it as a common, almost ubiquitous source of meaning. Musical experiences can be more or less meaningful, shifting from dark and devastating to upbeat and profound. Even the rhythms seem to resonate with us, compelling us to move in accordance with the beat. This is explored in the musical entrainment literature, which finds that music binds and shapes both our personal and interpersonal experience in predictable yet culturally sensitive ways (Clayton et al., 2020). Here, rhythm is essential for producing entrainment, as are attention and anticipation.

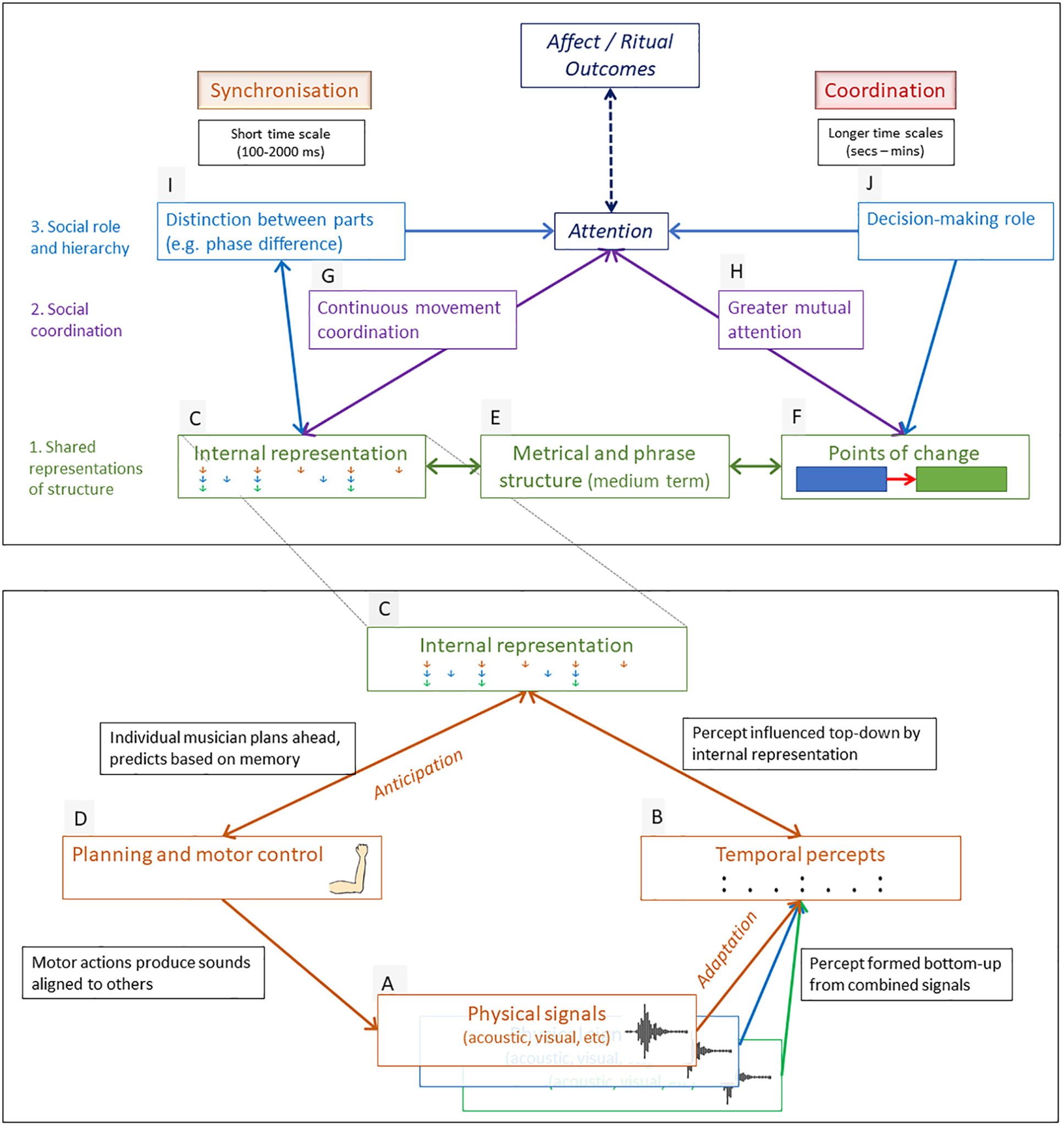

Figure 4 - Musical Entrainment model (Clayton et al., 2020)

Beyond music, we encounter other forms of entrainment. Brainwave entrainment syncs auditory, tactile, and visual stimuli to target specific, EEG-measurable voltage fluctuation patterns. This research is being explored as a means to treat ADHD (López, 2020), improve sleep quality (Abeln et al., 2014), and strengthen meditation (Lavallee et al., 2011). This last application is especially relevant, as meditation is associated with both peak experiences and PiMSes. Commonly, brainwave entrainment targets the theta (4-8Hz) and/or alpha (8-12Hz) frequency bands, which are found in relaxed, hypnagogic, and deep sleep states (Lavallee et al., 2011). Intentional entrainment could be a way to target the correlates of altered states, because it is uniquely positioned as a controllable, quantitative, predictable method of integrating conscious and nonconscious information.

Central to entrainment is attention–if something fails to grab our attention over time, we do not entrain. Increasing entrainment is therefore a matter of selecting stimuli that reliably arrest our attention. This is non-trivial, in that we crave change but appreciate stability. There are, however, fascinating visual and auditory stimuli that match these demands. Recreational explorers of psychedelic experiences (called “psychonauts”) have built and developed tools that enhance and shape their experiences (called “journeys”).

For the sake of the present experiment, we’re committing to inducing peak experiences through external stimuli (versus psychedelics, which directly alter neural dynamics), but the experience-shaping tools that psychonauts find endlessly fascinating are at least moderately fascinating to us, even when sober. We will single out one of these and examine whether we can use it to produce the effect we’re looking for:** immediately meaningful experience that significantly alters narrative meaning, both in the short and long-term. **

Hopalong Orbits

Form Constants

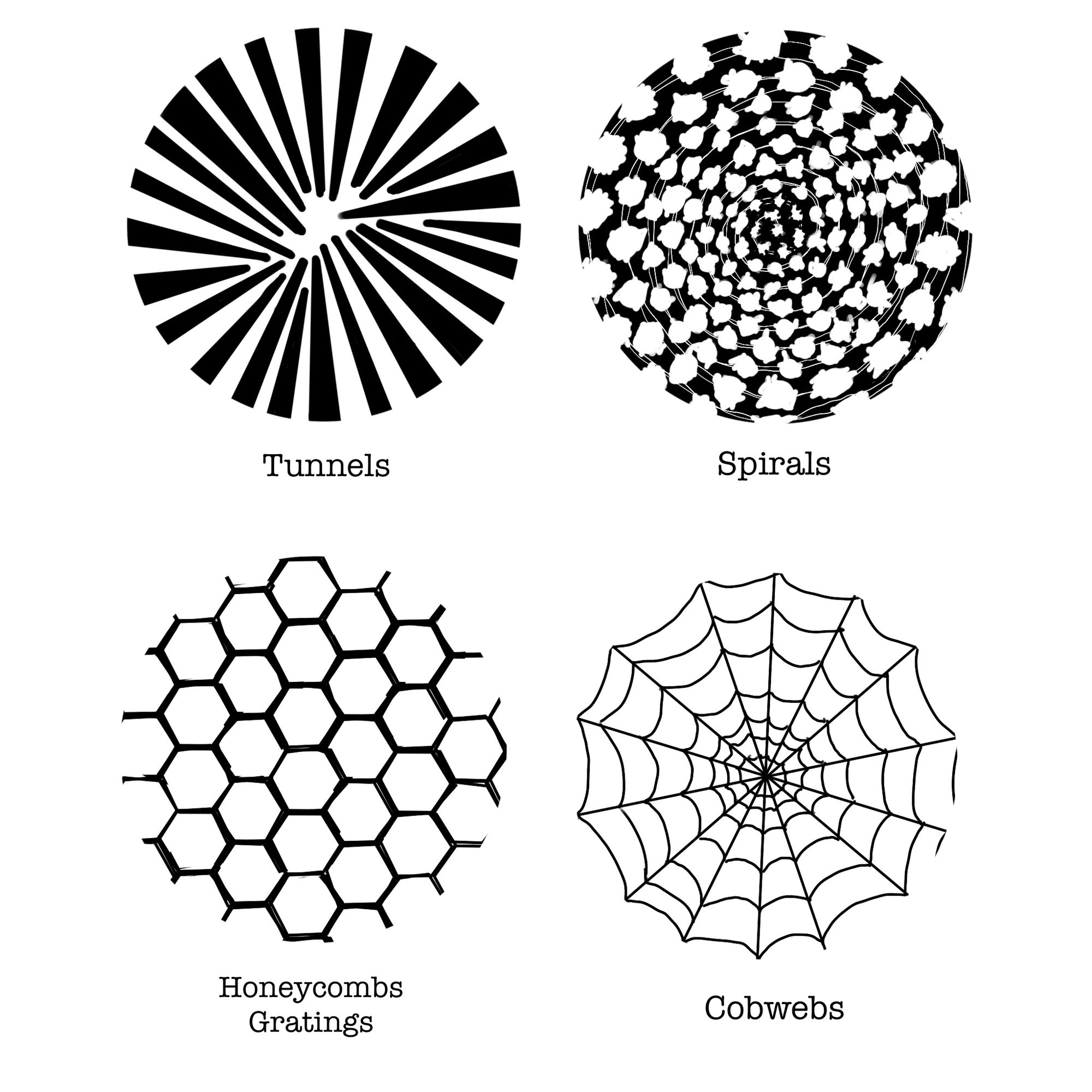

One feature common to psychedelic experiences is the perception of _form constants _(Bressloff et al., 2002). These are recurring geometric patterns that Klüver identified through self-exploration of mescaline.

Figure 5 - Klüver’s Form Constants found in his exploration of mescaline (Bressloff et al., 2002)

These patterns are found in both nature and in art–from the earliest pieces (Lewis-Williams et al., 1988) to now. Psychedelic experiences involve a layering of these patterns over both direct visual experience (in the nucleus of consciousness) and in imaginings. Further investigation has shown that these are found in entoptic phenomena–our eyes capture light with physical neuronal arrays that produce form constant patterns at the lowest levels (the eyes and V1 region of the brain) (Entoptic Phenomenon - an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics, n.d.). Because of this, we might entertain several possibilities about the intrinsic interestingness of form constants:

- We’re always processing these patterns–they’re just suppressed (Winkelman, 2017)

- The patterns are intrinsically, aesthetically interesting

- The patterns evoke hypnagogia

- The patterns decrease_ functional integrity_ of the self-referencing processes in the default mode network (DMN) (R. Carhart-Harris et al., 2014)

- Viewing these patterns evokes past experiences of altered states

These are all candidate explanations but need not be considered independently. It could be that we are simultaneously suppressing form constants, finding them pretty, hypnotic, and evocative of past altered states. They might also show up in the brain as decreased functional integrity within and between the DMN and other regions. The bottom line is this: we find form constants both attentionally arresting and aesthetically interesting. And, fortunately, variations to these patterns can sustain our interest.

Subjective effects

Besides form constants, psychonauts widely report changes to color perception, where reds are experienced as more red and novel, indescribable shades are reported. These changes are accompanied by many more, documented in detail in a wiki format (Subjective Effect Index - PsychonautWiki, 2022). Among the most accessible and relevant are experiences of recursion, environmental patterning/cubism, and symmetrical texture repetition. These are somewhat reproducible–with 3D graphical rendering tools–it’s possible to simulate these features of psychedelic tripping, to approximate the visual features of a psychedelic trip.

Barry Martin’s Hopalong Orbits Visualizer

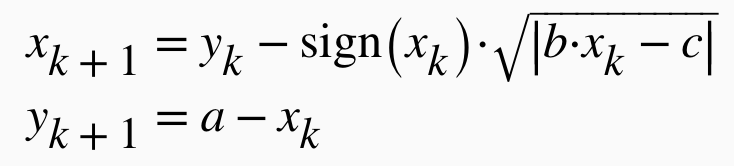

Barry Martin’s Hopalong Orbits Visualizer uses a relatively straightforward fractal attractor algorithm to generate recursive, patterned, repetitive patterns (Hopalong Attractor - Maple Help, n.d.):

By providing a set of initial variable values and randomly shifting these each iteration, the visualizer produces a series of cartesian points that result in form constants. These are also given random colors each iteration and are made to rotate slightly and move towards the experiencer at a controllable velocity. Additionally, users may shift their perspective slightly as they experience forward movement through the simulated space.

Figure 6 - Randomly generated fractal sequence, taken from Barry Martin’s Hopalong Orbit Visualizer

The orbital patterns exhibit recursion, environmental patterning/cubism, and symmetrical texture repetition, all of which are typical perceptions found in psychedelic experience. This experience also supports some of our enumerated points on form constants: They are (2) interesting, (3) hypnotic, and (5) evocative of past experiences with altered states. As for whether (1) is true–this merits further investigation. (4) might be readily verified as well–if we can demonstrate that merely observing these patterns is sufficient to acutely decrease functional integrity in the DMN, this would provide direct evidence for our proposed (correlates of altered states → altered states) model. But we need not involve brain fMRI to support this. Instead, it would be similarly compelling to use a version of the Visualizer to demonstrate the possibility of transforming sensory stimuli into altered states, marked by their immediate and narrative meaning.

The Effects of Sensory Stimulation on the Generation of Meaning

Leveraging everything discussed here, we’ve developed a pilot study to investigate the potential of generating meaning from sensory stimulus.

Tools